Hello World! Welcome back 🎉 What a week (or two) it has been, full of yet more WTH moments. While there are many different cloud-native platforms, tools and services that I could centre this latest instalment around this week; I thought I’d take the opportunity to discuss an interesting project that I came across in my day to day life.

Whilst deploying my first kubeadm master node, I was faced with the decision of which pod network add-on to use 👀. Of course, WTH I thought. Yet another moment that I had my false sense of understanding extinguished 🧯. After doing a little bit of searching on the internet, I just found a bunch of people yelling ‘use calico, it just works’, so I decided heck why not, let’s just do it.. I applied the yaml file I was prompted with, and away I went.

Fast forward a couple of days, and I heard the word ‘Antrea’. If you’ve not figured it out by now, names like Tanzu, Octant, Istio, Helm, Prometheus and Antrea, have a certain ring to them that makes the mind go ‘definitely some open-source project related to Kubernetes’. So of course I start asking more questions, and it turns out that Antrea is a pod networking add-on for Kubernetes; just in the way that Calico is 🤔. It was at this point that I thought, “ok sure… it seems that I must take the time to understand what this whole pod network add-on business means in the world of cloud-native, and work out what is going on”. So good news, I’m going to drag you all along with me, let’s go!

Brief Side-Note

The aim of this blog as a whole is to make it inclusive for all, so in my first post, I added some links/content that step through the basics of containers and kubernetes. So don’t fear, exciting content that will explain all is only a few clicks away!

What is Pod Networking? 🔗

So we’re back to Kubernetes again (surprise, surprise). And this time we’re taking a look at pod networking. So far in my Kubernetes voyage (sailing pun intended), I have tried to wrap my head around what every kubernetes object is, and how it stitches together. To be frank with you all, asking questions such as ‘how do pods get assigned IPs’ was not at the top of my list of curiosities 😂. As far as I was concerned initially, I started minikube or GKE, and all the networking just folded silently into the background.

At a basic level, container networking is a mechanism through which containers can optionally connect to other containers, hosts and external networks, like our good friend the internet. Simple capabilities are provided by our base layer container runtimes such as docker 🐳, but more advanced capabilities require additional drivers and plugins. Of course, on a platform such as kubernetes, designed to allow people to command, control, connect, and mould their micro-services in any which way they like, a smart networking solution is of high importance.

So in a world where processes are spinning up, spinning down, shifting and changing all the time, in multiple places; a framework is required to manage and configure their networking. In a model like this it’s required, as quite frankly… I don’t back myself to keep up with the management of this stuff… do you? Therefore the container runtime utilises something called a Container Networking Interface (CNI), to handle all of this chaos!

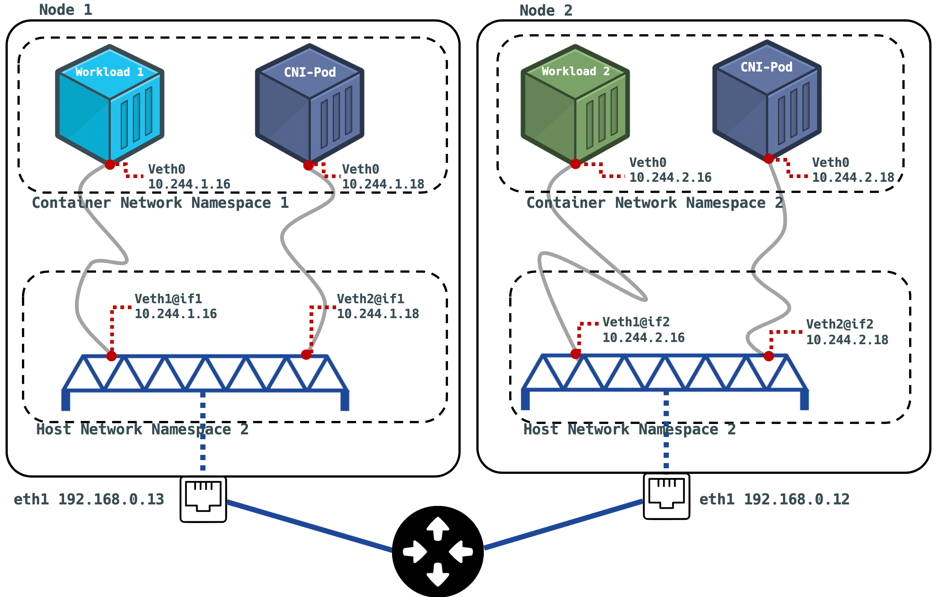

These plugins provision and manage the IPs of the containers within the runtime, and get informed when said container dies, so resources can be cleaned up. Of course the IPs provisioned for the containers are of a different format to what is seen for the hosts sitting on your home-lab network for instance. While your physical host that is running Kubernetes may have an IP subnet of ‘192.168.0.0/16’, your pod network will likely use a subnet of the form ‘10.244.0.0/16’ (this is what mine uses 😄). so this begs the question… “sure, two pods in a node can easily have a chat with one another… but what if that pod wants to talk to the node on their network… or even worse, what if they want to talk to a pod on another node 🤯?” Well, the plugin helps us out here by establishing a ‘veth’ virtual interface pair. one situated in the local pod network namespace,and another on a ‘bridge’, sitting in the hosts namespace. The bridge is a virtual switch that is capable of forwarding traffic between network segments, as we discussed above. I like to visualise these links sat on a bridge as akin to those gateways in stranger things between the real world and the upside down… except in this case we’re travelling between network namespaces. If you haven’t watched it then my compelling argument for you to is right there ✊.

After copious amounts of effort, I have taken the time to create a diagram that I feel describes this mystical situation below without (too much) complexity. Let’s envision a scenario where we have configured two nodes to run our containerised workloads on; workload 1 and workload 2. As you can see in the diagram, each node is connected to a router on the private network with a subnet of 192.168.0.0/24, and have been leased an IP with DHCP. Say for example that in this instance, we have kubernetes installed to orchestrate the containers, have deployed each workload so they run on a separate node (node 1 and 2). Now upon using kubectl to feel like a wizard and magically get container networking configured on our cluster of nodes. In reality, a few things are actions are being executed (unfortunately you’re not a real wizard yet). The containers on each node are assigned a unique IP within the subnet range of the container network namespace (this can be declared by the user upon install). After some investigation of my own cluster, the 3rd octet of each pods IP corresponds to the node they’re running on (e.g. 10.244.1.18 for node 1), pretty neat. Now what also happens, is a Daemonset is created by the CNI installer. This is an object declaration that ensures all nodes run a copy of a certain pod. In the diagram, this is where our ‘CNI-Pod’ comes from 😎. This is the component that handles the declaration of the bridge interface (dark blue looking object in diagram), so that the containers can leak out their packets to the big bad world 🥴!

A lot to take in? I know. Don’t worry though, I also didn’t quite get it the first time either (hence missing last weeks post 🥊). I will also embed a video at the bottom of the page that I found helpful.

Ok ok, that’s enough. Tell me about Antrea

Before we dive in, I just thought i’d mention that the public Github repository for Antrea is available here. The project is still very young, and they’re looking for members of the open-source community to join in and contribute. Are you what they’re looking for? Go check it out. If not, you should definitely still check out the README 🙂.

So, where was I… aha ‘Project Antrea’. released as a part of the portfolio of open-source projects spearheaded by VMware under the guise ‘Tanzu’, this networking solution is developed primarily for the kubernetes platform, and works very much in the same way as described in the muddled up collection of words in the previous section. So how is it different to previous CNIs? Well, Antrea harnesses a multilayer (OSI layer 2-7) virtual switch software called Open vSwitch to handle the data plane, operating at layer 3⁄4. In other words the virtual interfaces (veth and bridge) mentioned above are in this case handled using OVS. The benefits brought about by using such a technology within the CNI are:

- High Performance. Technologies that aim to optimise data flow at every level, from data-link layer up to application layer have been used to optimise this technology to transmit packets as quickly and efficiently as possible.

- Portability. One fantastic thing about OVS is it’s support for any platform; including windows, Linux and any cloud distribution. This is great for enterprise users with a plethora of different environments that are communicating with one another.

- Operations. Through the design of OVS, Antrea is able to provide metrics for many existing monitoring tools and protocols (such as Prometheus?… OK not yet… more content on this coming soon 😲).

- Flexibility and Extensibility. OVS allows the user to create an overlay network for there cluster based on a number of protocols, such as VXLAN, Geneve, GRE and STT. This gives the user a lot of power if they have particular compatibility needs for the infrastructure that sits beneath (casual wink to VMware NSX 😉).

One final feature that I think is worth noting is a plugin for Octant, which is a platform for developers to easily view and better understand a kubernetes cluster through a beautiful UI 🤗. Of course, this is also provided by VMware, and it is very easy to deploy, and I recommend that you play with it if you have a cluster for it to utilise.

Wrapping Up 🎁

Ok, so we have battled through the (somewhat) magical way that kubernetes pods get allocated a subnet, and moreover their own individual IP address so that they really can function automatically all over the world. But we’ve also taken a look at project Antrea, and demystified that ‘WTH’ moment that I encountered just a couple of weeks ago.

My learning on the subject of container networking is still developing, so I hope that this post made enough sense to be useful, and as always brought some benefit to your life. If so, any comments or feedback would be heavily appreciated, and if you spot any errors or things to correct, the same goes.

I will sign out by embedding a YouTube video (as promised) of a KubeCon conference presented by Kristen Jacobs from Oracle titled ‘Container Networking from Scratch’. This helped me greatly in getting my head around the basic concepts, so thought it would be worth referencing.